Draft

Limitations

It’s a pity to announce that the project did NOT accomplish all of its stated goals during the period of URA funding:

- Take-off from the ground

- Take-off from the water surface

- Fly in the air

- Controlled motion in the air

- Move on the water surface

- Controlled motion on the water surface

- Controlled motion in the water

Despite exciting initial results, by the fall of 2022, I was finding it increasingly difficult to move forward.

- Control of the ornithopter required high expertise in vortex aerodynamics and underactuated systems, which was far beyond my knowledge.

- The micro-coreless motors I could afford were limited in power (my prototype was hard to take off, and there was no room to continue adding equipment) and didn’t support precise speed and position control. Micro DC servo motors might work but be too expensive for the URA grant.

With the mutual agreement between the CUHK-Shenzhen URA committee and me, this project was finally terminated in October 2022.

Reflection — What Bionic Robotics Taught Me

Although this project did not achieve the expected results, I still gained a lot from it, not only in knowledge, but also in research. This project was a watershed moment for me. Before doing this project, my mantra was to build cool robots. This project forced me to think hard about the science behind the robots.

When building this ornithopther prototype, I found an interesting phenomenon — not all flapping-wing robots can take off from the ground by themselves. Some existing robots (DelFly, Hummingbird, Robobee, MetaFly) have demonstrated the ability to take off from the ground, while others (小隼, MetaBird, BionicSwift) need to be released from the air. The reasons for this are not explained in detail in the papers on these robotic systems.

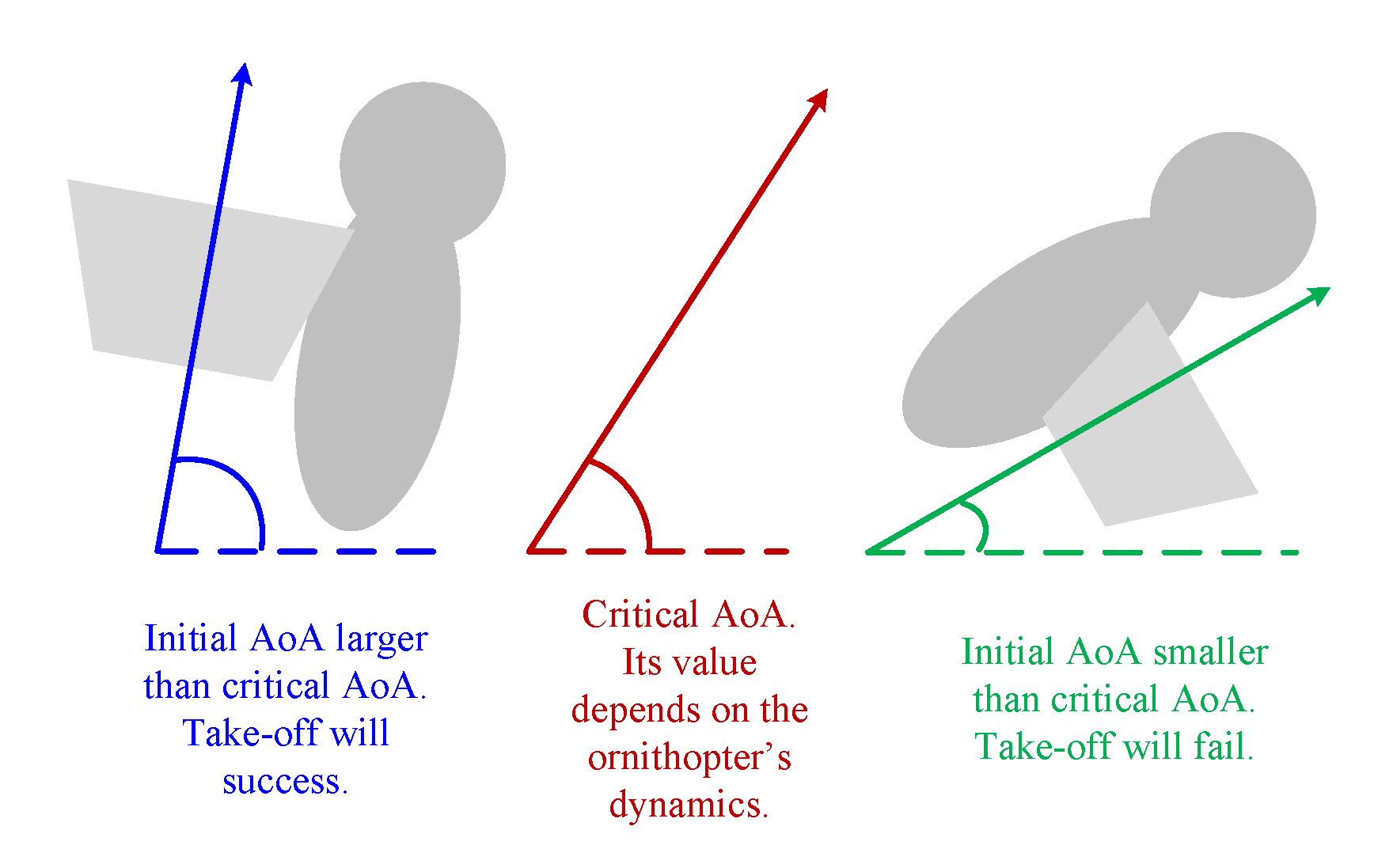

Both successful and unsuccessful take-offs from the ground were observed when my prototype was in flight tests. Through long-term experiments and control variates, I eventually found a key factor — the initial angle of attack (AoA) of the wings. I found there was a critical AoA (although i can’t quantify). If and only if the initial AoA was large than the critical AoA, the robot could generate sufficient lift to take off. Sometimes the robot even created downward pressure when the initial AoA was less than the critical AoA.

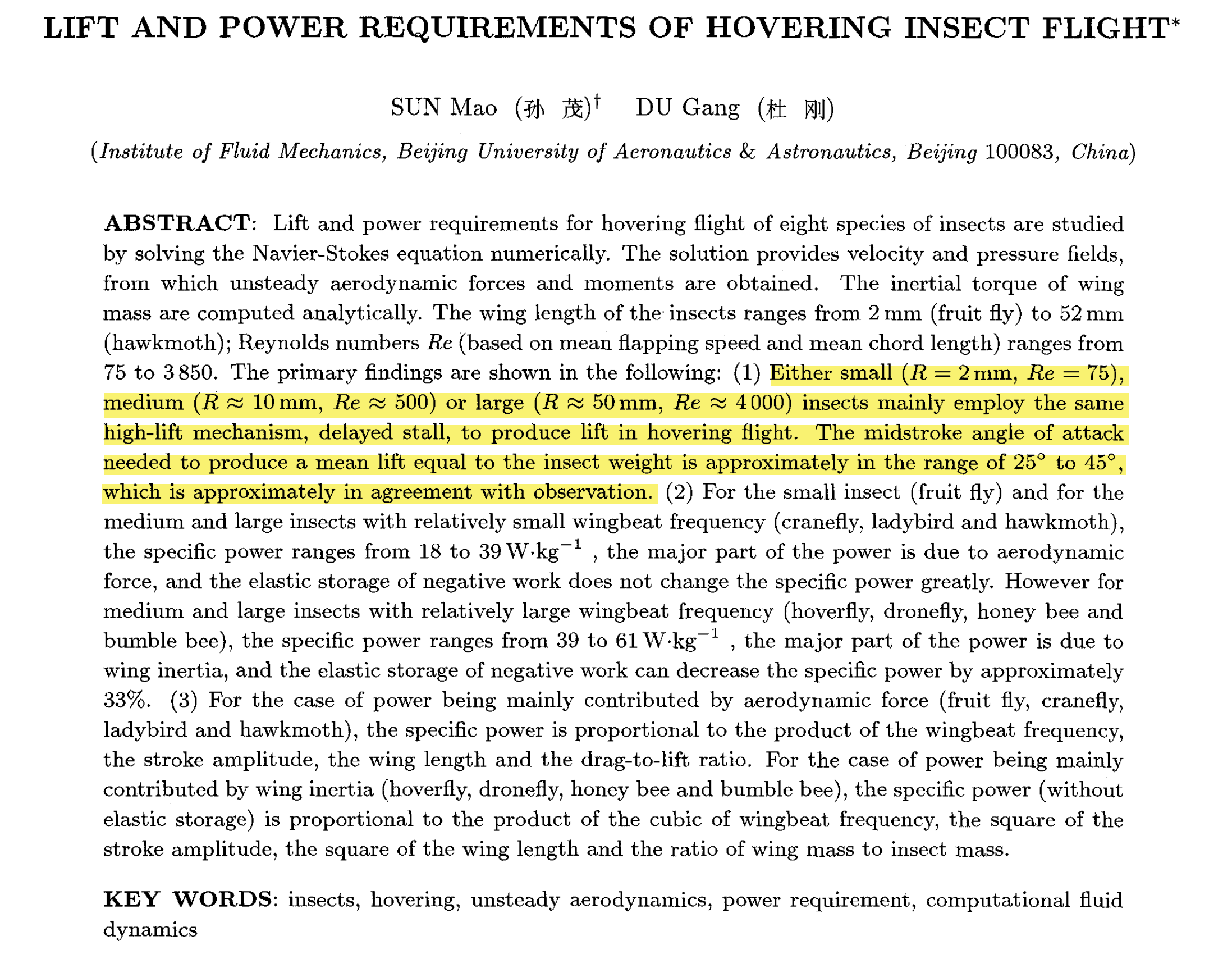

I have to admit that I did have this as my new academic discovery for a while, and even imagined that I would be famous in the academic world for pointing out this law. Until one day when I searched the literature, I found that this law and the principle behind it had been written in a paper (Lift and Power Requirements of Hovering Insect Flight) published almost 20 years ago. ![]()

Although it turned out to be an oolong in the end, the ecstasy of verifying a natural law through my own efforts is something I will never forget in my life. This fantastic experience made me realize for the first time that engineering can be used as a tool to understand natural science. As Feynman’s famous saying goes, “What I cannot create, I do not understand.”

Demonstrations

Table of contents:

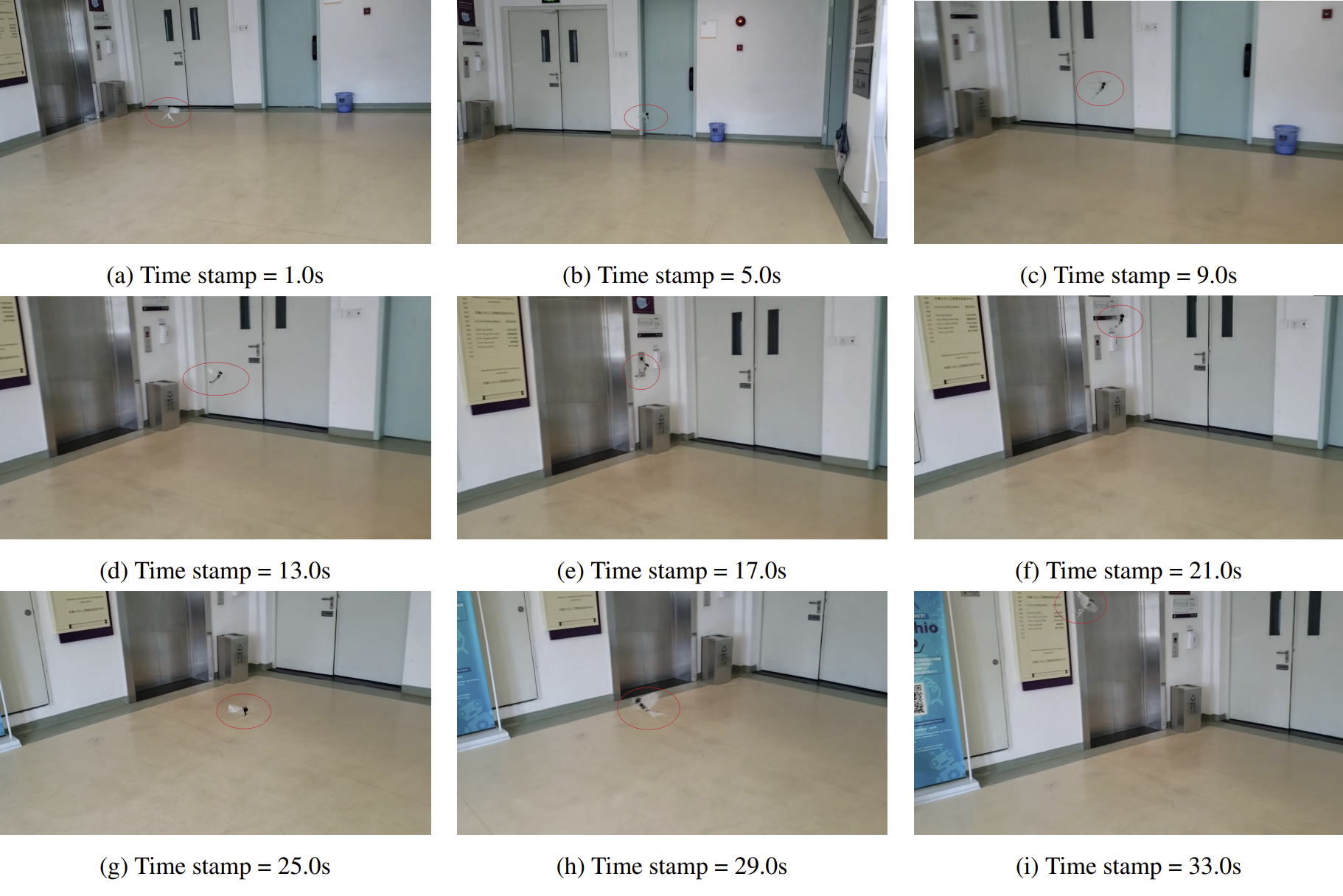

Take-off and stay in the air

Here are the sequential screenshots of the take-off process:

Here is the video demo:

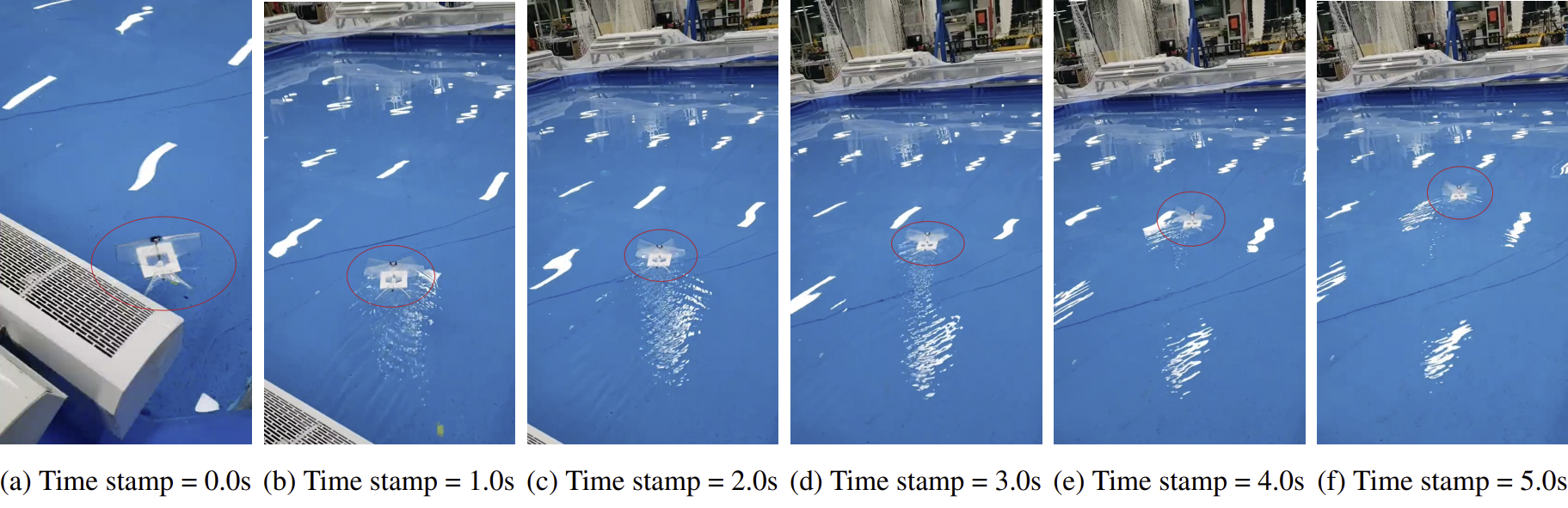

Advance on the water

Here are the sequential screenshots of advancing on the water surface by flapping wings:

Here is the video demo:

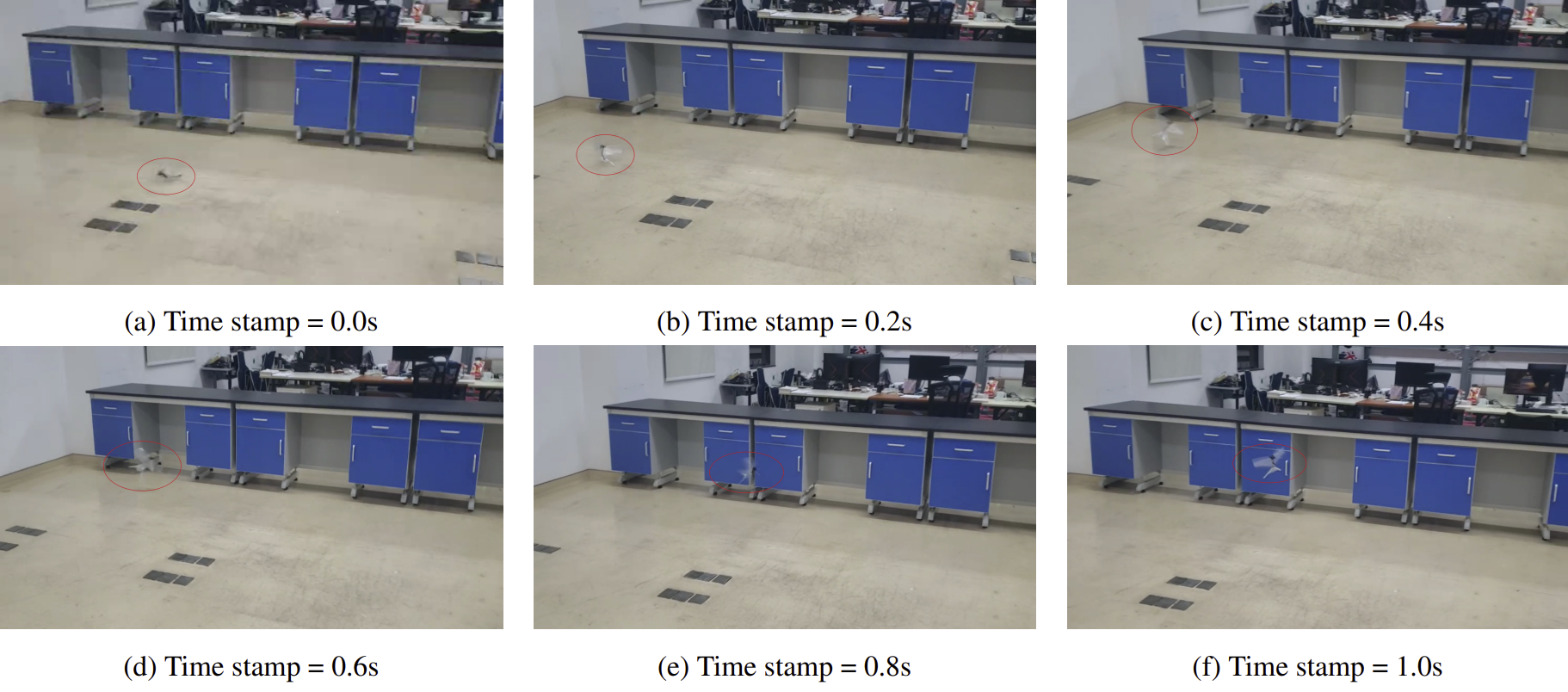

Take-off successfully - large AoA

Here are the sequential screenshots of a successful take-off, with large initial angle of attack (AoA):

Here is the video demo:

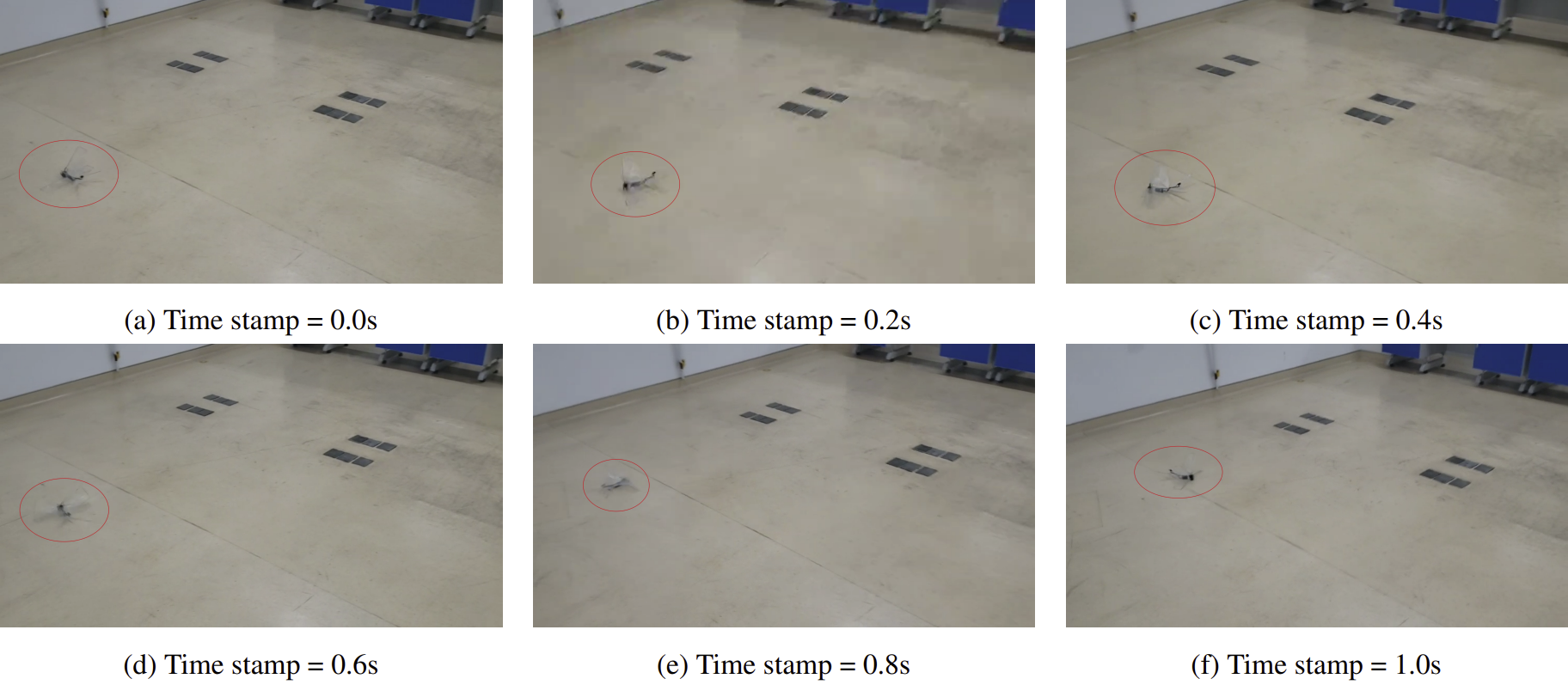

Take-off failed - small AoA

Here are the sequential screenshots of a failed take-off, with small initial angle of attack (AoA):

Here is the video demo:

Related

Some projects & products I referred to:

- DelFly — Micro Air Vehicles Laboratory, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands.

- Hummingbird — Bio-Robotics Lab, Purdue University, USA.

- Robobee — Harvard Microrobotics Lab, Harvard University, USA.

- 小隼 — Northwestern Polytechnical University, China.

- MetaFly and MetaBird — Bionicbird, France.

- BionicSwift — Festo, Germany.

Some papers I found useful for understading insect flight:

- M. H. Dickinson, F.-O. Lehmann, and S. P. Sane, “Wing Rotation and the Aerodynamic Basis of Insect Flight,” Science, vol. 284, no. 5422, pp. 1954–1960, 1999.

- M. Sun and D. Gang, “Lift and Power Requirements of Hovering Insect Flight,” Acta Mechanica Sinica, vol. 19, pp. 458–469, 10 2003.

- K. S. Wu, J. Nowak, and K. S. Breuer, “Scaling of the Performance of Insect-Inspired Passive-Pitching Flapping Wings,” Journal of the Royal Society Interface, vol. 16, 2019